I’m 49 years old and have been writing professionally as a marketing communication specialist since 2001. The most agonizing part of my job? Crafting that dazzling intro. Apparently, in writing for enjoyment and personal satisfaction, I must grapple with the same issues. So, I’ll just get to it.

I have a short list of big life questions. They relate to the topics and themes I’m drawn to again and again. I’ve started Imagination Nexus to explore one of them:

How can imagination, which is both an idea and a mental activity beyond our current reality, make a difference and improve the real world?

Allow me to explain how I got to this point.

Since the time I could hold a book, I’ve read. During quieter seasons of life, I’ve read voraciously. This, unfortunately, isn’t one of those seasons, but I do tend to reflect on what I read (and listen to) a lot more carefully these days. Perhaps it’s because of the divorces—defined relationally as a marriage of 22 years and spiritually as adherence to Evangelicalism for more than 30 years. (I remain a Christian.) Or maybe it’s the therapy, which has helped me process many of the what’s and why’s of those breakups.

Whatever the reason, not only do I reflect, but I also take notes. Lots of them. I organize them, too. Over the years, they’ve become my “second brain.” I recently dubbed my notes a second brain after hearing Tiago Forte, an expert on productivity and founder of Forte Labs, describe what I do as part of having a second brain (or a personal system for knowledge management) in his talk, How to Think Creatively on Command. CODE—which stands for capture, organize, distill, and express—is the framework Forte has developed to describe the creative process.

I italicized the word “part” because I’m really good at the capture and organize half, but I never make time to distill and express for myself. Day in and day out as an entrepreneur in marketing communication, I complete the CODE process for clients (even though I’ve never thought of it that way), but I never complete it for me. It hit me when Forte said this:

“…sometimes people become information hoarders where they fall in love with the C in CODE. They fall in love with capturing because there is a bit of pleasure- it's like hunting. You get that little tidbit of knowledge, you save it in your little special place, and you're like, ‘Ah, I made progress. I acquired something valuable.’ But what I want to do is have people fall in love with the end of the process. The beginning of the process is great. The end of the process is even much, much better because that's when your thinking comes to fruition. That's when it all gets to live and stand on its own two feet as something apart from yourself.”

Okay, Tiago, I’m ready to fall in love with the end of the process, too.

Now, back to imagination.

Reimagining Imagination

As a young reader, one of my go-to genres was fantasy. Two writers in particular wrote stories that captivated me: J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. The scenes, the characters, the tales, and, most importantly, the meaning they created stayed in my thoughts for years after I read (and re-read) their books.

As an adult, I delved into some of Tolkien’s more mythical works, like The Silmarillion, and several of Lewis’s non-fiction works, including his autobiographical Surprised by Joy. It was the latter where I first encountered the notion that imagination meant more than just fun flights of fancy. In reflecting on his earliest childhood memories—around the age of six, seven, and eight—Lewis says he lived almost entirely in his imagination1, and that the “imaginative experience of those years now seems to me more important than anything else [emphasis mine].”

He goes on to relate “the memory of a memory.” For me, it’s become something similar because it moved me so much when I read it. He writes:

“As I stood beside a flowering currant bush on a summer day there suddenly arose in me without warning, and as if from a depth not of years but of centuries, the memory of that earlier morning at the Old House when my brother had brought his toy garden into the nursery. It is difficult to find words strong enough for the sensation which came over me; Milton's ‘enormous bliss’ of Eden (giving the full, ancient meaning to ‘enormous’) comes somewhere near it. It was a sensation of course, of desire, but desire for what? not, certainly, for a biscuit tin filled with moss, nor even (though that came into it) for my own past. [Greek: Ioulian pothô]2 —and before I knew what I desired, the desire itself was gone, the whole glimpse withdrawn, the world turned commonplace again, or only stirred by a longing for the longing that had just ceased. It had taken only a moment of time; and in a certain sense everything else that had ever happened to me was insignificant in comparison.”

After sharing two additional “glimpses” of the imaginative, including one in Beatrix Potter’s Squirrel Nutkin and another in Longfellow’s Saga of King Olaf, Lewis says, “The reader who finds these three episodes of no interest need read this book no further, for in a sense the central story of my life is about nothing else.”

The common quality between the three glimpses for Lewis? “It is that of a unsatisfied desire which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction. I call it Joy…”

I did read the rest of the book, which was faith affirming in ways I only vaguely remember. But I have never forgotten this passage, in part because—in juxtaposing imagination, desire, and joy—Lewis shifted my paradigm. I realized imagination wasn’t just for kids and creatives.

Starting with Lewis seems like a great place to begin my quest.

Imagination: A Vehicle to Get You From Desire to Joy

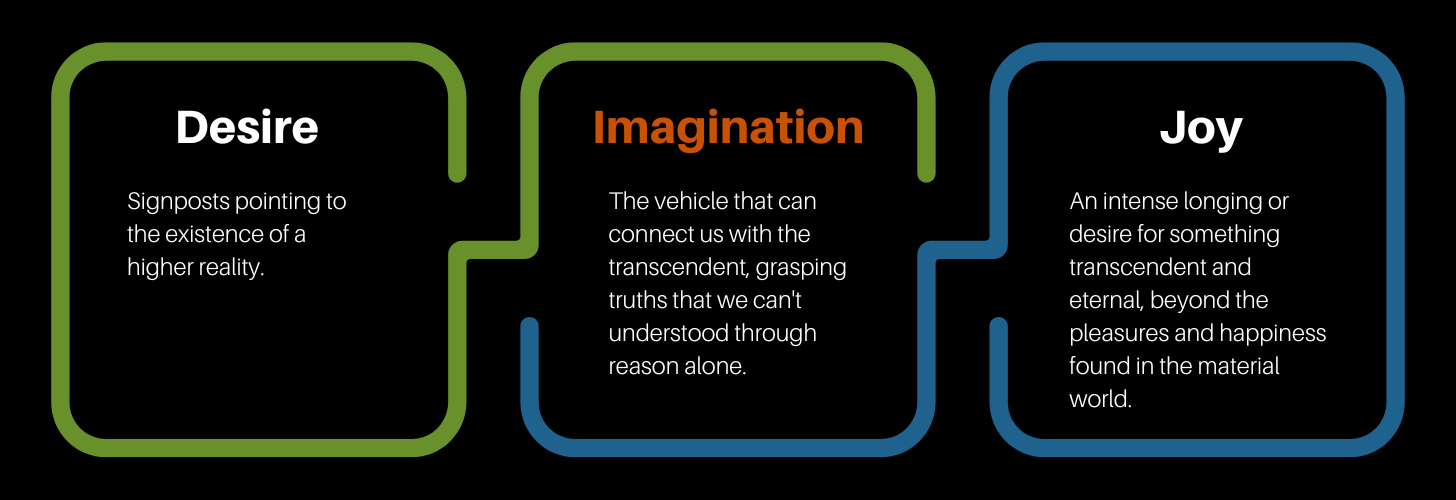

My first observation about imagination is that Lewis3 believes it’s closely connected with desire and joy. As a well-known Christian apologist, his conclusions are, of course, deeply influenced by his own spiritual experiences. However, faith aside, I think there’s value in considering the interconnectedness of imagination, desire, and joy simply because they are essential for understanding and analyzing human experience, behavior, and culture.

Lewis appears to see these abstract concepts on a sort of continuum. Joy is out there somewhere—an intense longing or desire for something transcendent and eternal, beyond the pleasures and happiness found in the material world. Desire is where we are, serving as an internal signpost or a driving force; it points us to the existence of a higher reality and leads us to seek truth and meaning. Imagination, then, is the vehicle between them, giving us a pathway to connect with aspects of reality we can’t fully understand or grasp through human reason or empirical knowledge alone. It enables us to create new worlds and possibilities. When applied to things beyond our personal needs and wants, imagination can involve a deep sense of communion with something greater than ourselves.

Given our hyperfocus on the individual in the U.S., I assume many if not most Americans would read Lewis’s words about imagination and compartmentalize them as self help of some kind. But, with my goals in mind, I am looking for more:

Does this definition of imagination only apply to an individual person, or can it be used to think about making a difference in a community and in society more broadly?

Does it matter if imagination leads to joy as Lewis defines it? If yes, why?

I’m especially interested in the process of creating new worlds and possibilities—and I don’t mean in a science fiction sort of way. One of the reasons I even have this big question is because I desire things that aren’t present in this world but could be. My list is long, but it can be distilled down to this:

Equitable access to the resources every human being needs in order to flourish, no matter your skin color, age, gender, class, or sexual orientation.

Some people believe this is impossible to achieve on earth; why try? Others think it’s possible, but only when everyone is forced to live under a specific set of rules. Still others believe the “power of positive thinking” holds the answer; they want “good vibes only.” All those frameworks are flawed.

It’s especially important to me that anyone who reads this knows I don’t conflate imagination with positive thinking. Sadness, struggle, and suffering are just as much a part of the human experience as imagination. Author, professor, and cancer survivor Kate Bowler brings much needed balance to the positivity narrative, and I think it’s worth mentioning here:

“For the last century, Western culture has been dominated by ideologies of positivity. Optimism is big business. It is a message of megachurches and fitness gurus. Peloton instructors and multi-level marketing schemes selling leggings or essential oils.

It is the dominant commercial messaging for every glittering Instagram influencer in the multi-billion dollar health and wellness industry. We can heal ourselves by mastering our minds. Just believe the that the universe has your back.

[That's when] Positivity becomes a kind of poison…4

And I won’t be adding to that poison.

I do, however, wonder where this journey will take me. If I were writing a book, readers would expect a thesis with supporting evidence and helpful conclusions laid out neatly. Well, welcome to a bit of freewheeling because I’m on the hunt for those conclusions. For now, I’ll leave the rest to my imagination.

C.S. Lewis, "Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life" (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1955), chap. 1, "The First Years."

Oh, I desire too much.

C.S. Lewis is considered an authoritative author and teacher for several reasons:

He was an accomplished academic, having held positions at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities. His work as a scholar in literature, particularly in medieval and Renaissance studies, showcased his intellectual capabilities and his ability to engage deeply with various subjects.

Over the years, C.S. Lewis's writings have had a significant impact on readers, inspiring countless people in their spiritual and intellectual pursuits. His works continue to be studied and discussed, and his influence is felt not only in the realm of Christian thought but also in the wider literary and philosophical spheres.

Lewis's writings often address universal themes and questions, making his work relevant even decades after it was initially published. His exploration of topics such as love, morality, human nature, and the search for meaning ensures that his writings remain significant and continue to resonate with readers today

K. Bowler, "Positivity is POISONOUS, says author KATE BOWLER in her provocative new book," Daily Mail, 14 October 2021, [Online]. Available: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-10089201/amp/Positivity-POISONOUS-says-author-KATE-BOWLER-provocative-new-book.html. [Accessed: 7 May 2023].

![Black and white image of C.S. Lewis sitting at a desk looking at papers. Words superimposed say, "...the imaginative experience of those [childhood] years now seems to me more important than anything else." Black and white image of C.S. Lewis sitting at a desk looking at papers. Words superimposed say, "...the imaginative experience of those [childhood] years now seems to me more important than anything else."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff7d6d970-b421-4260-8ad5-5de56548fe28_1456x1048.png)